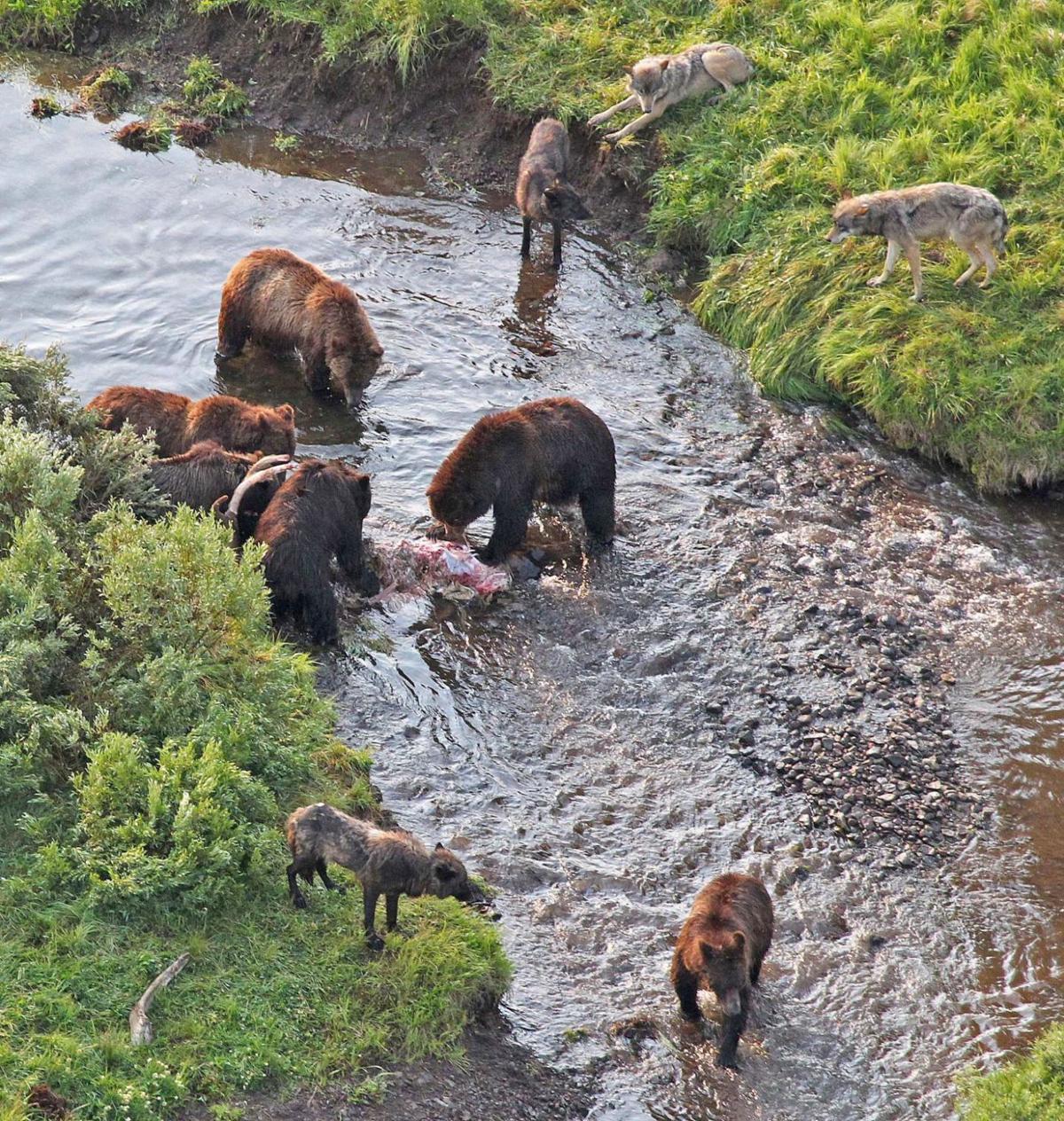

Canine distemper virus is an extremely important pathogen infecting wild carnivores worldwide. Similar to other Morbilliviruses, canine distemper virus (CDV) is an acute, highly immunizing, highly transmissible pathogen causing high juvenile mortality. CDV dynamics are generally poorly understood at least partially because CDV infects species in seven carnivore families, and in wild settings, requires very large multi-host communities to persist. For example, CDV cannot be sustained within in the diverse carnivore community of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (~18-million hectares encompassing Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks). Despite this, there were three major CDV outbreaks in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) from 1995–2014. Many species were exposed to the virus during these outbreaks and it is likely cross-species transmission occurred by close contact via aerosols, oral, respiratory, or ocular fluids. Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) are often witnessed forcing wolves (Canis lupus) off of prey carcasses, and the bears will feed directly after wolves feed on the carcass. This led scientists to investigate the cross-species transmission potential among grizzlies and wolves in the GYE.

A team of researchers investigated the correlation in CDV dynamics in wolves and grizzly bears using 30 years of serological data. They hypothesized that grizzly seroprevalence would increase after wolves were reintroduced into the GYE in 1995 and that CDV exposure would be correlated to the timing of wolf CDV outbreaks. They used Bayesian state-space models to account for the fact that there is uncertainty in actual time of infection or exposure using serological data. The scientists that investigated this system included: Paul Cross, Frank van Manen, and Mark Haroldson from USGS, Mafalda Viana (U. Glasgow), Emily Almberg (Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks), Daniel Bachen (Montana Natural Heritage Program), CIDD researchers Ellen Brandell and Peter Hudson, and Daniel Stahler and Doug Smith (NPS).

Cross et al. used Bayesian a state-space model to estimate annual CDV infection hazard and account for the unknown timing of infection and potential test errors. Cross et al. developed and fit numerous models that differed by the inclusion of the effects of previous years within or across species, or by allowing wolf exposure to influence bear exposure within a year. They also explored different titer thresholds that determine exposure status because this decision almost always must be made when using serological assays, and the selected titer cutoff may influence results. The team then selected the best model and assessed the effect of different prior distributions.

The top models suggested that wolf infections slightly increased the probability of grizzly bear infections in a given year, although this was partially dependent upon the selected priors. However, these results were not realized at the lowest titer threshold, supporting the use of a moderate to conservative threshold. The grizzly bear population did not have notable widespread outbreaks like the wolf population regardless of titer threshold. Despite the use of a state-space hierarchical a model and, for wildlife species, a long time series, it was difficult to assess disease dynamics among these hosts. Regardless, this research by Cross et al. is a crucial step towards understanding the decision-making involved with analyzing serological data, as well as accounting for both observational and process error in a useful modeling framework.

Synopsis written by Ellen Brandell

Photo credit: National Park Service

Publication Details

P Cross, F van Manen, M Viana, E Almberg, D Bachen, E Brandell, M Haroldson, P Hudson, D Stahler, D Smith

Estimating distemper virus dynamics among wolves and grizzly bears using serology and Bayesian state-space models

Journal: Ecology and Evolution

ece3.4396

DOI Reference