Efforts to quell Ebola have strained the health systems of West Africa. Humanitarian aid and local health care in countries affected by the ongoing Ebola crisis have been forced to shift focus from routine disease-prevention measures, such as vaccination, to handle the more dire and imminent needs of Ebola-treatment. Recent work by CIDD researcher Matt Ferrari and colleagues Saki Takahashi, Bryan Grenfell and Jessica Metcalf at Princeton University, William Moss, Shaun Truelove,and Justin Lessler at Johns Hopkins University, and Andrew Tatem from University of Southampton, has explored how Ebola treatment has interfered with Measles vaccination and could lead to increases in the measles-susceptible population, a situation prime for an ensuing epidemic.

Using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from the DHS Program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Princeton University graduate student Saki Takahashi created measles vaccination maps to identify the number and geo-location of unvaccinated children in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, the three countries primarily affected by Ebola virus disease. The researchers used the measles vaccination maps containing data from before the epidemic to then estimate the spatial distribution of unvaccinated individuals in the future assuming 6,8,12, or 18-months of disrupted vaccination. Unvaccinated individuals were assumed to be measles-susceptible. The researchers then used estimates of the measles transmission rate calculated using statistical methods developed by Ferrari and colleagues at Penn State and published case fatality rates to estimate the impact that a growing susceptible pool could have on a measles epidemic size and measles deaths.

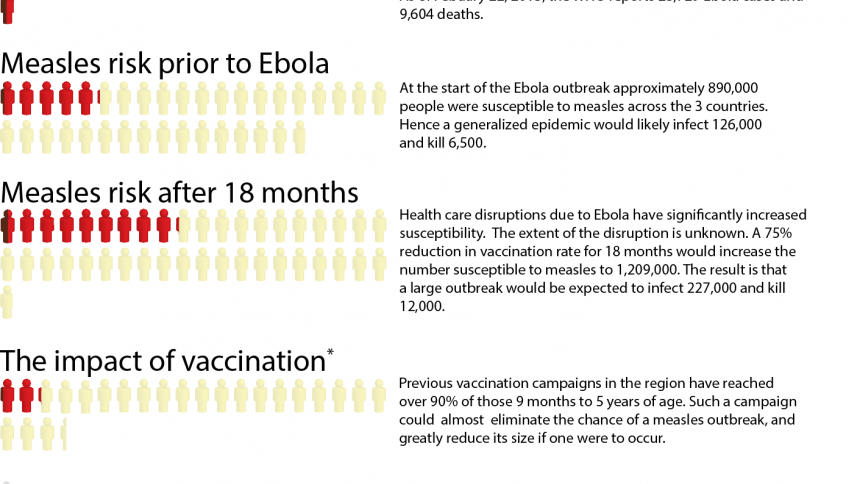

Assuming a 75 percent reduction in measles vaccination rates as a result of Ebola-related healthcare disruptions, the results of the work suggest there will be over 1 million additional measles-susceptible children, in addition to the number of children already susceptible before healthcare disruptions. This increase in the susceptible pool led to model predictions that a future measles epidemic in West Africa could cause hundreds of thousands of cases and lead to as many as 1 thousand to 16 thousand additional deaths. The threat of sickness and death due to measles adds insult to injury for countries already overwhelmed by the spread of Ebola.

Historically, measles epidemics have been known to coincide with disruptions in health care infrastructure or crisis, but Ferrari and colleagues suggest that perhaps this time, we can act to prevent measles before more lives are lost. The work, published in Science, suggests that campaigns to vaccinate children could be incorporated into humanitarian relief efforts now, to lessen the degree of routine-healthcare disruption during the Ebola crisis. The paper, available here, alludes to other preventable diseases with prevention-efforts impaired in recent months. Ferrari and colleagues have issued an early warning that campaigns targeting alternative distribution of vaccines and other disease-prevention supplies should be implemented during the current Ebola crisis, as waiting until the Ebola epidemic is over may be too late to prevent a large number of deaths from preventable and devastating diseases more common than Ebola.

Synopsis written by Jo Ohm.

Publication Details

Takahashi S, Metcalf J, Ferrari MJ, Moss WJ, Truelove SA, Tatem AJ, Grenfell BT, & Lessler J

Reduced vaccination and the risk of measles and other childhood infections post-Ebola

Journal: Science

347: 1240-1242

DOI Reference